Curated with aloha by

Ted Mooney, P.E. RET

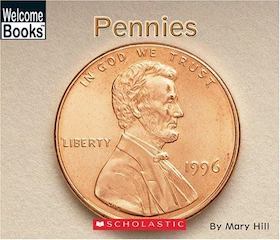

What juice or liquid cleans pennies best?

United States Mint image

United States Mint image

Guidance for your Science Fair project

1. You will probably hear the words "hypothesis", "variable", "control", "observations", "conclusions", "demonstrate" vs. "prove".

- Your hypothesis is your best guess about some science fact, and it's what your experiment will try to demonstrate or disprove. If your best guess is that lemon juice will clean pennies better than milk or saltwater, then your hypothesis is "Lemon juice cleans pennies better than milk or saltwater" and your experiment will try to demonstrate it (your experiment may actually end up not proving, or even disproving, your hypothesis, of course).

- An independent variable is something which you choose to vary, and a dependent variable is something that may change as a consequence. For example, if you choose to skip breakfast (choice = independent variable) you will consequently be hungry (consequence = dependent variable). If you choose to buy a dollar hamburger, you will consequently have one less dollar in your pocket.

For your science experiment, you will choose to vary something (independent variable) in order to observe the consequence (dependent variable) to try to thereby demonstrate [the truth of] your hypothesis. If you choose to clean a penny with a heated liquid, the penny may consequently be cleaner or less clean than if you chose to use the liquid at room temperature. The temperature is the independent variable, the consequent cleanliness is the dependent variable.

- You know what the word control means as a verb (as an action word), but what it means as a noun may confuse you because the scientists have slanged it up, and "the control" is not something that is doing the controlling, it's something that is being controlled :-(

The control is something that is NOT being varied, so that when you claim that some consequence that you have observed (dependent variable) is the result of you changing something (independent variable), you have information on what would have happened if you hadn't made the change. This is pretty tricky, so let's give an example before we move on!

Suppose your hypothesis is that hot lemon juice will clean a penny better than cold lemon juice. So you put one penny in cold lemon juice for 30 seconds and you drop one penny into boiling lemon juice, intending to leave it for 30 seconds. You want to retrieve your penny from the boiling juice but your mom yells "Whoa, you may burn yourself! Wait till it cools". If the penny in the juice that was hot gets cleaner, now you're not sure whether it's because the juice was hotter or because the penny was in it longer. So you now need a control, you need to put a penny in cold lemon juice and leave it there for the whole time the penny was in the hot juice.

- Observations are things you saw, heard, smelled, or measured that are relevant to your experiment. Sometimes scientists guess wrong about what was relevant, but still we try to apply common sense. If the pennies clean up quicker when you use heated juice, that is a relevant observation. Whether you were wearing a red dress or a blue one when you did the experiment isn't a relevant observation because common sense tells you that the color of your dress will not effect the outcome of this experiment; but the color of your dress might be very relevant in a different experiment about whether bulls will chase you :-)

Observations are truths that are not very subject to opinion. You never change your observations because your hypothesis changes or your conclusions change or other students got different results. If you saw tiny gas bubbles collect on your penny, that's what you observed no matter what anyone else saw or didn't see.

- Conclusions are what you believe your experiment demonstrated. For example, "In my experiment, lemon juice cleaned pennies better than milk, but not as well as saltwater".

- Demonstration vs. Proof. Your experiment will demonstrate something but it is much less likely to "prove" it, and to the extent possible you should use the word "demonstrate" rather than "prove". Here's an example. Suppose you flip a coin 10 times and it comes up heads 7 times. You repeat the experiment a second time and it comes up heads 7 times. You know darn well that you haven't "proved" that coins will land heads up 7 out of 10 times. Before submitting your report, look for the word "prove" and remove it unless you are sure that you have "proved" it rather than just demonstrated it.

2. Do your experiment first, the research later. Why? Ever heard the term "Junk Science"? Junk science happens when you know the answer you want to get, so you use stupid but nice sounding reasons to throw away your contradictory observations, pretend to yourself that you didn't see some things, and you just keep at it until you get the answer you wanted by making the "rules" for the experiment as wacky as necessary :-)

That's not science, that's poison! As a young person trying to please the teacher, you will find it very difficult to fight the temptation to practice junk science if you know the answer that you think you're "supposed to get".

3. Don't call the brown color on pennies "rust"! It's not. "Rust" means iron oxide -- the corrosion product of steel or iron. There is no steel or iron in pennies (with the exception of pennies from 1943, which were steel with a coating of zinc because of the shortage of copper during WWII), so pennies can't rust.

4. Pennies before 1982 were solid copper, about 95-97 percent pure and the composition can be found on the website of the U.S. Mint at www.usmint.gov). Pennies from 1983 and later are a zinc core with a thin copper plating (pennies from 1982 can be either solid copper or zinc core). Post-1982 pennies will behave funny if a liquid gets through a scratch or pinhole and reaches the zinc, so you should not mix the two types in an experiment. Use pre-1982 pennies if

you can.

5. You are not really "cleaning" the pennies, you are dissolving the copper oxide "tarnish" on them, allowing it to wash away, exposing the underlying copper metal. This is important to note because things that are good at removing soils, like soap, detergent, and shampoo will be of no use in dissolving the copper tarnish. But some things that are poor cleaners like lemon juice plus salt (a mild acid), vinegar

⇦in bulk on

eBay

or

Amazon [affil link] plus salt (a mild acid), and Coke & Pepsi (mild acids) will be good at removing the tarnish.

6. The acidity of the juice has a bit to do with it, but salt has a bigger effect. You can "clean" a penny a little bit and very slowly with lemon juice or vinegar (mild acids), but put a dash of salt in the lemon juice and the penny will turn orange with a quick rub. People say that ketchup and taco sauce are good cleaners for pennies, but read the ingredients: "Tomatoes, Vinegar, Salt . . . "

7. Your teacher probably doesn't fully understand this subject. It is very complicated to understand why salt plays such an important part in dissolving the tarnish, yet the salt won't work without the acid. One explanation, which is not exactly correct nor completely wrong, is that salt plus acid makes hydrochloric acid, which is a quite powerful acid.

8. The purpose of this experiment is not to get the "right" answer, because there isn't one! The strength of juices varies by season, and the country where they were grown, and the ripeness of each individual fruit. Plus, fruit juices contain hundreds of different chemicals that complex, chelate, sequester, buffer, and otherwise make the results of your experiment variable. Coke & Pepsi are secret formulations; we don't even know what is in them! Someone may claim that the acid in soft drinks is what is doing the tarnish removal, but when they don't even know what else is in them, how can that be anything but a guess?

9. What you should learn from the experiment is a piece of "the scientific method". Before you do anything else, get a notebook or composition pad for the experiment and number the pages so you won't be tempted to rip a page out if you later don't like what you wrote earlier. This is called a lab book. Then use a pen, not a pencil, because you don't want to be able to erase anything. Then write down everything you do in setting up the experiment, and everything you see, smell, hear, or otherwise observe. Keep jotting down the date and time as you do this. If you accidentally drop your chewing gum into the vinegar bowl, write it down because it might affect the results and be a relevant observation (how are we to know?). If you have written something that you think is completely wrong and you should remove it, strike it through once but leave it legible.

10. Remember the difference between "observations" and theories / explanations / hypotheses / conclusions. What sets observations apart from the rest? You can't change them; they are not opinions or guesses, they are facts! If you saw that your penny in vinegar was covered with tiny gas bubbles, it doesn't matter whether your classmates' pennies were or not, yours were. Period! As you rethink your theories and conclusions to account for what you've seen, you never go back and change an observation. Your lab book will hopefully get you an A whether your answers were what the teacher expected or not.

Here are some Q&A threads on the subject if you wish to read still more:

If this didn't find what you were looking for, please Search the site. Good luck! |